Embattled E.ON and RWE turn to the government and the courts for help

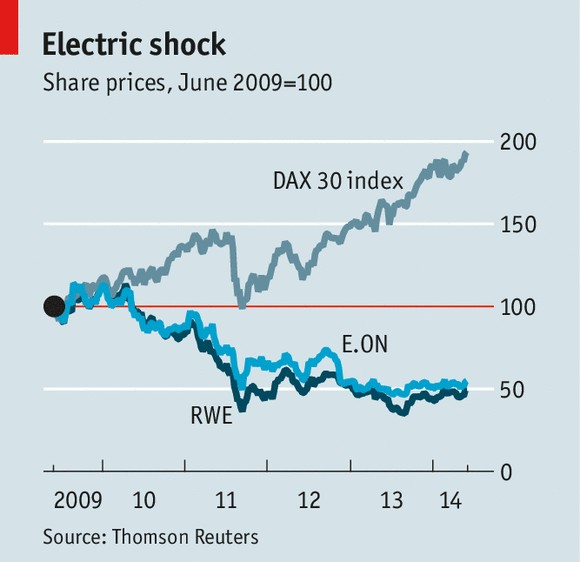

Jun 7th 2014, BERLIN - RECENT years have brought little but bad news for Germany’s power generators. Having overinvested in gas- and coal-fired plants before the financial crisis, the two largest, E.ON and RWE, ended up with excess capacity in the ensuing downturn—just as lavish subsidies to wind- and solar-power producers were bringing a host of new competitors to the market. After the nuclear accident at Fukushima in Japan in 2011, the German government decided that all nuclear plants in the country must close by 2022, bringing forward the huge costs of decommissioning them. To cap it all, ever more industrial consumers of electricity have gone “off the grid”, generating their own power. Shares in the two power giants have fallen by almost half in the past five years, whereas Germany’s DAX stockmarket index has almost doubled in that time (see chart).

The power generators are now hoping that the government, having done so much to undermine their business, will take pity on them. First, they are floating the idea that it could create a nuclear “bad bank”—an equivalent to the state agency that was set up to assume the worst bits of a big mortgage bank that collapsed during the crisis. The power firms would give this new official fund the €36 billion ($49 billion) or so that they have already saved towards the eventual decommissioning of their nuclear plants, and keep contributing to it. But taxpayers would bear the risk that the costs turned out higher than expected.

So far the government is refusing to consider the proposal. However, John Musk of RBC Capital Markets, a broker, thinks that something may still come of it. Indeed, a few influential politicians, such as Bärbel Höhn, who chairs the parliamentary environment committee, have argued that such a fund may be preferable to risking the bankruptcy of the power companies, in which case the reserves they have already built up might be wiped out. The second way in which the power companies want the government to help is by creating a “capacity market”, in which it would subsidise them to keep some coal- and gas-fired stations that would otherwise be uneconomic standing by for times when wind and solar power is not enough to meet demand, to avert blackouts. But such a market looks years off, at best.

Legal aid

The power firms also hope the courts will come to their aid. In April a Hamburg court ruled that the nuclear-fuel tax the government has been charging them since 2011 was unlawful. The case now goes to the German constitutional court and perhaps the European Court of Justice, but in the meantime E.ON and RWE will, between them, get back €2.2 billion in provisional refunds. A bigger windfall may be in prospect shortly, when another court rules on their demand for €15 billion in compensation over the government going back on its original decision to extend the lives of their nuclear plants. Mr Musk reckons that if both court cases go the companies’ way, it could more than double the profits they will make next year.

In all, the power generators are beginning to see a way out of what RWE’s boss, Peter Terium, has called a “vale of tears”. Once they restore their profitability and cut their liabilities, they can return to investing for growth.

But in what? They have come late to the renewable-energy business; and going big on wind and solar just when the government is trying to cut its subsidies may not be a wise move. The companies would like to move further into electricity retailing—but their retail businesses in Britain have made E.ON and RWE (known there as Npower) highly unpopular, and the opposition Labour Party is threatening to freeze their prices if it wins next year’s election. The emerging markets? A good idea in theory, but E.ON’s heavy investments in Turkey and Brazil have not produced the expected profits. The path out of the vale of tears appears to be strewn with rocks.